JFK Assassination: Jim Garrison & the Clay Shaw Trial (1969)

The Clay Shaw trial was a highly publicized court case that took place in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1969. The trial was led by Jim Garrison, the District Attorney of Orleans Parish, who was seeking to prove that Clay Shaw, a prominent businessman and former director of the International Trade Mart in New Orleans, was involved in a conspiracy to assassinate President John F. Kennedy.

The trial was based on Garrison's belief that there was a vast conspiracy involving a number of individuals and organizations, including the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), to assassinate President Kennedy. Garrison alleged that Clay Shaw was one of the key players in this conspiracy, and had used his position as the head of the International Trade Mart to facilitate the assassination.

The trial began on January 21, 1969, and lasted for several weeks. Garrison called a number of witnesses to testify, including a former CIA agent named Victor Marchetti, who claimed to have inside knowledge of the agency's involvement in the assassination.

However, the trial took a dramatic turn on February 21, 1969, when a witness named Perry Raymond Russo took the stand. Russo claimed that he had been present at a party where Clay Shaw, Lee Harvey Oswald, and David Ferrie, a local pilot and alleged co-conspirator in the assassination plot, had discussed their plans to kill President Kennedy. Russo's testimony was seen as a major breakthrough for Garrison's case, and led to a flurry of media attention.

Despite Russo's testimony, the trial was ultimately unsuccessful in proving Shaw's guilt. Shaw's defense team argued that Garrison's case was based on hearsay and unreliable witnesses, and that there was no direct evidence linking Shaw to the assassination plot. On March 1, 1969, the jury returned a verdict of "not guilty" on all charges, and Shaw was acquitted.

The Clay Shaw trial remains a controversial and heavily debated topic to this day, with many conspiracy theorists continuing to believe that Shaw was involved in the assassination of President Kennedy. However, the trial was ultimately seen as a failure for Garrison, who faced criticism for his handling of the case and his use of unverified witnesses.

James Carothers Garrison (born Earling Carothers Garrison; November 20, 1921 – October 21, 1992)[3] was the District Attorney of Orleans Parish, Louisiana, from 1962 to 1973. A member of the Democratic Party, he is best known for his investigations into the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and prosecution of New Orleans businessman Clay Shaw to that effect in 1969, which ended in Shaw's acquittal. The author of three books, one became a prime source for Oliver Stone's film JFK in 1991, in which Garrison was portrayed by actor Kevin Costner, while Garrison himself also made a cameo as Earl Warren.

Early life and career

Earling Carothers Garrison was born in Denison, Iowa, in 1921.[4][5][6] He was the first child and only son of Earling R. Garrison and Jane Anne Robinson who divorced when he was two years old.[3] His family moved to New Orleans in his childhood, where he was raised by his divorced mother. He served in the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War II, having joined the year before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. After the war he obtained a law degree from Tulane University Law School in 1949. He then worked for the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) for two years where he was stationed with the Seattle office.[7] Leading up to the Korean War era, Garrison joined the National Guard, even applying for active duty with the Army in 1951, but because of recurring nightmares of past missions Garrison was then relieved of duty by the Army. Remaining in the Guard when it became apparent that he suffered from shell shock due to his numerous bombing missions flown during World War II,[8] leading one Army doctor to conclude that Garrison had a "severe and disabling psychoneurosis" which "interfered with his social and professional adjustment to a marked degree. He was considered totally incapacitated from the standpoint of military duty and moderately incapacitated in civilian adaptability."[9] Yet, when his record was reviewed further by the U.S. Army Surgeon General, he "found him to be physically qualified for federal recognition in the national army."[10] Upon returning again to civilian life, Garrison worked in several different trial lawyer positions before winning election as New Orleans District Attorney, starting with his first of three terms in January 1962.[7]

District attorney

In the years prior to winning office as New Orleans District Attorney in 1961, Garrison worked for the New Orleans law firm of Deutsch, Kerrigan & Stiles from 1954 to 1958, before he first became an assistant district attorney. Garrison became a flamboyant, colorful, well-known figure in New Orleans but was initially unsuccessful in his run for public office. He lost a 1959 election for criminal court judge. In 1961, he ran for district attorney and won against incumbent Richard Dowling by 6,000 votes in a five-man Democratic primary. Despite lack of major political backing, his performance in a television debate and last-minute television commercials facilitated his victory.

Once in office, Garrison cracked down on prostitution and the abuses of Bourbon Street bars and strip joints. He indicted Dowling and one of his assistants for criminal malfeasance, but the charges were dismissed for lack of evidence. Garrison did not appeal. Garrison received national attention for a series of vice raids in the French Quarter, staged sometimes on a nightly basis. Newspaper headlines in 1962 praised Garrison's efforts, "Quarter Crime Emergency Declared by Police, DA. – Garrison Back, Vows Vice Drive to Continue – 14 Arrested, 12 more nabbed in Vice Raids." Garrison's critics often point out that many of the arrests made by his office did not result in convictions, implying that he was in the habit of making arrests without evidence. However, assistant DA William Alford has said that charges would more often than not be reduced or dropped if a relative of someone charged gained Garrison's ear. Alford said Garrison had "a heart of gold."[11]

After a conflict with local criminal judges over his budget, he accused them of racketeering and conspiring against him. The eight judges charged him with misdemeanor criminal defamation, and Garrison was convicted in January 1963. In 1964, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the conviction and struck down the state statute as unconstitutional.[12] At the same time, Garrison indicted Judge Bernard Cocke with criminal malfeasance and, in two trials prosecuted by Garrison himself, Cocke was acquitted.

Garrison charged nine policemen with brutality, but dropped the charges two weeks later. At a press conference, he accused the state parole board of accepting bribes, but could obtain no indictments. Critical of the state legislature, Garrison was unanimously censured by it for "deliberately maligning all of the members".[13]

In 1965, running for reelection against Judge Malcolm O'Hara, Garrison won with 60 percent of the vote.

Kennedy assassination investigation

As New Orleans D.A. in late 1966, Garrison began an investigation into the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, after receiving several tips from Jack Martin that a man named David Ferrie may have been involved in the assassination.[14] The result of Garrison's investigation was the arrest and trial of New Orleans businessman Clay Shaw in 1969, with Shaw being unanimously acquitted less than one hour after the case went to the jury.[15][16][17]

Garrison was able to subpoena the Zapruder film from Life magazine. Thus, members of the American public – i.e., the jurors of the case – were shown the movie for the first time. Until the trial, the film had rarely been seen, and copies were made by assassination investigator Steve Jaffe working with Garrison. Jaffe had obtained an early generation copy from French Intelligence which he shared with David S. Lifton.[18] In 2015, Garrison's lead investigator's daughter released his copy of the film, along with a number of his personal papers from the investigation.[19]

Garrison's key witness against Shaw was Perry Russo, a 25-year-old insurance salesman from Baton Rouge, Louisiana. At the trial, Russo testified that he had attended a party at anti-Castro activist David Ferrie's apartment. At the party, Russo said that Lee Harvey Oswald (who Russo said was introduced to him as "Leon Oswald"), David Ferrie, and "Clem Bertrand" (who Russo identified in the courtroom as Clay Shaw) had discussed killing President Kennedy.[20] The conversation included plans for the "triangulation of crossfire" and alibis for the participants.[20]

Russo's version of events has been questioned by some historians and researchers, such as Patricia Lambert, once it became known that part of his testimony might have been induced by hypnotism, and by the drug sodium pentothal (sometimes called "truth serum").[21] An early version of Russo's testimony (as told in Assistant D.A. Andrew Sciambra's memo, before Russo was subjected to sodium pentothal and hypnosis) fails to mention an "assassination party" and says that Russo met Shaw on two occasions, neither of which occurred at the party.[22][23] However, in his book On the Trail of the Assassins, Garrison says that Russo had already discussed the party at Ferrie's apartment before any "truth serum" was administered.[24] Scambria said that the party information was simply accidentally left off the notes of his encounter with Russo. Throughout his life, Russo reiterated the same account of being present for a party at Ferrie's house along with the Mr. Bertrand where the subject of Kennedy's potential assassination had come up.[25][26]

Garrison defended his conduct regarding witness testimony, stating:

Before we introduced the testimony of our witnesses, we made them undergo independent verifying tests, including polygraph examination, truth serum and hypnosis. We thought this would be hailed as an unprecedented step in jurisprudence; instead, the press turned around and hinted that we had drugged our witnesses or given them posthypnotic suggestions to testify falsely.[27]

In January 1968, Garrison subpoenaed Kerry Wendell Thornley – an acquaintance of Oswald's from their days in the military – to appear before a grand jury, questioning him about his relationship with Oswald and his knowledge of other figures Garrison believed to be connected to the assassination.[28] Thornley sought a cancellation of this subpoena on which he had to appear before the Circuit Court.[29] Garrison charged Thornley with perjury after Thornley denied that he had been in contact with Oswald in any manner since 1959. The perjury charge was eventually dropped by Garrison's successor Harry Connick Sr.

During Garrison's 1973 bribery trial, tape recordings from March 1971 revealed that Garrison considered publicly implicating former United States Air Force General and Deputy Director of the Central Intelligence Agency Charles Cabell of conspiracy in the assassination of Kennedy after learning he was the brother of Earle Cabell, the Dallas mayor in 1963.[30] Theorizing that a plot to kill the president was masterminded out of New Orleans in conjunction with the CIA with cooperation from the Dallas police department and city government, Garrison tasked his chief investigator, Pershing Gervais, of looking into the possibility that General Cabell had stayed in the city's Fontainebleau Motel at the time of the assassination.[30] The Washington Post reported that there was no evidence that Gervais ever followed through with the request and that there was no further mention of General Cabell in Garrison's investigation.[30]

US talk radio host David Mendelsohn conducted a comprehensive interview with Garrison which was broadcast in 1988 by KPFA in Berkeley, California. Alongside Garrison, the program featured the voices of Lee Harvey Oswald and JFK filmmaker Oliver Stone. Garrison explains that cover stories were circulated in an attempt to blame the killing on the Cubans and the Mafia but he blames the conspiracy to kill the president firmly on the CIA who wanted to continue the Cold War.[31]

Later career and death

In 1973, Garrison was tried and found not guilty by the jury for accepting bribes to protect illegal pinball machine operations. The prosecutor was Gerald J. Gallinghouse the United States Attorney for Eastern District of Louisiana, who was seeking to halt public corruption.[32] Pershing Gervais, Garrison's former chief investigator, testified that Garrison had received approximately $3,000 every two months for nine years from the dealers. Acting as his own defense attorney, Garrison called the allegations baseless and claimed that they were concocted as part of a U.S. government effort to destroy him because of Garrison's efforts to implicate the CIA in the Kennedy assassination. The jury found Garrison not guilty. In an interview conducted by New Orleans reporter Rosemary James with Pershing Gervais, Gervais had admitted to concocting the charges.[33]

In the same year, Garrison was defeated for reelection as district attorney by Harry Connick Sr. On April 15, 1978, Garrison won a special election over a Republican candidate, Thomas F. Jordan, for Louisiana's 4th Circuit Court of Appeal judgeship, a position for which he was later reelected and which he held until his death.[34]

In 1987, Garrison played Judge Jim Garrison in the film The Big Easy, and was featured in The Men Who Killed Kennedy series, beginning in 1988.

After the Shaw trial, Garrison wrote three books on the Kennedy assassination, A Heritage of Stone (1970), The Star Spangled Contract (1976, fiction, but based on the JFK assassination), and his best-seller, On the Trail of the Assassins (1988). A Heritage of Stone, published by Putnam, places responsibility for the assassination on the CIA and says the Warren Commission, the Executive Branch, members of the Dallas Police Department, the pathologists at Bethesda, and various others lied to the American public.[35] The book does not mention Shaw or Garrison's investigation of Shaw.[35]

Garrison's investigation received widespread attention through Oliver Stone's film, JFK (1991),[36] which was largely based on Garrison's book as well as Jim Marrs' Crossfire: The Plot That Killed Kennedy.[37][38] Kevin Costner played a fictionalized version of Garrison in the movie. Garrison himself had a small on-screen role in the film, playing United States Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren. Garrison also appears live and comments on the Shaw Trial in the documentary The JFK Assassination: The Jim Garrison Tapes, written and directed by actor John Barbour.

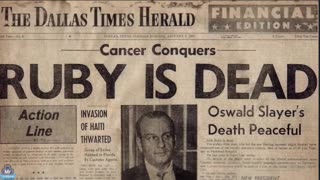

Garrison died of cancer in 1992, survived by his five children.[39][40] He is interred at Metairie Cemetery in New Orleans.[41]

Legacy

Political analyst and conspiracy believer Carl Oglesby was quoted as saying, "... I have done a study of Garrison: I come out of it thinking that he is one of the really first-rate class-act heroes of this whole ugly story [the killing of John F. Kennedy and subsequent investigation]."[42]

Garrison's investigation and trial of Shaw has been described by critics as "a fatally flawed case built on flimsy evidence that featured a chorus of dubious and even wacky witnesses."[43] Political commentator George Will wrote that Garrison "staged an assassination 'investigation' that involved recklessness, cruelty, abuse of power, publicity mongering and dishonesty, all on a scale that strongly suggested lunacy leavened by cynicism."[44] Former Orleans Parish district attorney Harry Connick Sr. said it was "a travesty of justice"[43] and that he "thought it was one of the grossest, most extreme miscarriages of justice in the annals of American judicial history."[45] Journalist Max Holland also described the investigation of Shaw as an "egregious miscarriage of justice".[46] Others who have called Garrison's case against Shaw a "miscarriage of justice" or "travesty of justice" include historian Alecia Long[47] and journalist Gerald Posner.[48] Conspiracy researcher Harold Weisberg called it a "tragedy".[49]

Conspiracy author David Lifton called Garrison "intellectually dishonest, a reckless prosecutor, and a total charlatan".[50] At the time, Garrison came under criticism from author and researcher Sylvia Meagher, who in 1967 wrote:

... as the Garrison investigation continued to unfold, it gave cause for increasingly serious misgivings about the validity of his evidence, the credibility of his witnesses, and the scrupulousness of his methods.[51]

According to Shaw's defense team, witnesses, including Russo, claimed to have been bribed and threatened with perjury and contempt of court charges by Garrison in order to make his case against Shaw.[52]

Filmography

Year Title Role Notes

1986 The Big Easy Judge

1991 JFK Earl Warren (final film role)

Selected bibliography

Books

A Heritage of Stone. Putnam Publishing Group (1970) ISBN 978-0399103988.

The Star Spangled Contract. New York: McGraw-Hill (1976). ISBN 978-0070228900. OCLC 1992214.

On the Trail of the Assassins. Grand Central Publishing (1981). ISBN 978-0446362771.

Articles

"The Murder Talents of the CIA". Freedom (April/May 1987)

References

Jim Garrison obituary accessed May 27, 2015

[Jim Garrison: His Life and Times, the Early Years, 2008]

Lambert, Patricia (2000). False Witness: The Real Story of Jim Garrison's Investigation and Oliver Stone's Film JFK. New York: M Evans and Company, Inc. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-4617-3239-6.

"Jim Garrison", Contemporary Authors Online, Gale, 2003.

"Jim Garrison", The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives, Volume 3: 1991–1993. Charles Scribner's Sons, 2001.

"Jim Garrison", Newsmakers 1993, Issue 4. Gale Research, 1993.

"Jim Garrison", On the Trail of the Assassins, Sheridan Square, 1988

Joan Mellen (2005). Jim Garrison, His Life and Times: The Early Years). pp. 33–36. ISBN 1-57488-973-7.

Associated Press, "Garrison Record Shows Disability", December 29, 1967. Warren Rogers, "The Persecution of Clay Shaw", Look, August 26, 1969, page 54.

Jordan Publishing; William Davy (May 1999). Let Justice Be Done: New Light on the Jim Garrison Investigation. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-9669716-0-6.

Joan Mellen (October 19, 2005). A farewell to justice: Jim Garrison, JFK's assassination, and the case that should have changed history. Potomac Books Inc. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-57488-973-4.

"Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 US 64 – Supreme Court 1964 – Google Scholar".

"Assassination Probe Conspiracy Being Kept Secret". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Spokane, Washington. AP. February 20, 1967. p. 2. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

David Ferrie, House Select Committee on Assassinations – Appendix to Hearings, Volume 10, 12, pp. 112–13.

Clay Shaw Interview, Penthouse, November 1969, pp. 34–35.

Clay Shaw Trial Transcripts, February 28, 1969, p. 47.

"Andrew 'Moo Moo' Sciambra, who worked on Jim Garrison investigation of JFK assassination, dies at age 75", July 28, 2010, by John Pope, The Times-Picayune

James H. Fetzer (1998). Assassination science: experts speak out on the death of JFK. Open Court Pub Co. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-8126-9365-2.

Morgan, Richard (November 20, 2015). "JFK assassination truthers will love this auction". New York Post. Retrieved November 23, 2015.

Testimony of Perry Raymond Russo, State of Louisiana vs. Clay L. Shaw, February 10, 1969.

"Perry Raymond Russo's Hypnosis: Making Testimony More Objective?". mcadams. 2007. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

"The Sciambra Memo". Retrieved September 17, 2010.

"Perry Raymond Russo: Way Too Willing Witness". Mcadams.posc.mu.edu. Retrieved September 17, 2010.

Jim Garrison (November 1988). On the trail of the assassins: my investigation and prosecution of the murder of President Kennedy. Sheridan Square Pubns. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-941781-02-2.

The Lighthouse Report, "The Last Testament of Perry Raymond Russo" Archived February 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Will Robinson, October 10, 1992.

The JFK Assassination: The Jim Garrison Tapes on YouTube, John Barbour, 1992.[dead link]

Jim Garrison Interview Archived October 22, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Playboy magazine, Eric Norden, October 1967.

"Writer Not Sure Oswald Assassin". The Miami News. January 10, 1968. Retrieved March 18, 2013.[permanent dead link]

"Writer Seeks Cancellation Of Subpoena". St. Petersburg Times. January 20, 1968. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

Kelso, Iris (September 16, 1973). "Garrison Planned To Link General To JFK Slaying" (PDF). The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. p. E 10. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

[1] Archived October 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

"Bill Crider, "This U.S. Attorney defies patronage system – He stays", October 4, 1977". Retrieved June 29, 2013.

"Pershing Gervais and the Attempt to Frame Jim Garrison" Archived August 30, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Peter R. Whitmey, The Fourth Decade, vol. 1, 4, May 1994, pp. 3–7.

[2][dead link]

Leonard, John (December 8, 1970). "The Story of Garrison Vs. Shaw". The Day. Vol. 90, no. 134. New London, Connecticut. p. 22. Retrieved August 24, 2015.

Fernandez, Jay A. (September 13, 2016). "On Truth: 'Snowden' and Oliver Stone's 10 Strongest Adaptations". Signature Reads. Penguin Random House. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

Fisher, Bob (February 1992). "The Whys and Hows of JFK". American Cinematographer. Archived from the original on January 27, 2019. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

Riordan, James (September 1996). Stone: A Biography of Oliver Stone. New York: Aurum Press. p. 351. ISBN 1-85410-444-6.

Lambert, Bruce (October 22, 1992). "Jim Garrison, 70, Theorist on Kennedy Death, Dies". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

"Epitaph For Jim Garrison: Romancing the Assassination" The New Yorker 30 November 1992 Retrieved January 12, 2012

"Brunswig Mausoleum | Classic Mausoleum Images and Information". Mausoleums.com.

Interview with Carl Oglesby. JFK: The Question of Conspiracy, Documentary. Dir. & Writ. Danny Schechter, Dir. Barbara Kopple (Regency Enterprises, Le Studio Canal, & Alcor Films: A Global Vision Picture, 1992)

"Former New Orleans DA, Kennedy prober, Jim Garrison dies". upi.com. UPI. October 22, 1992. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

Will, George (December 26, 1991). "'JFK': PARANOID HISTORY". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

Posner, Gerald (August 6, 1995). "Garrison Guilty. Another Case Closed". The New York Times Magazine. p. 41. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

Holland, Max (February 8, 2005). "Carson Showed Stuff When Confronted With Conspiracy". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on July 8, 2001. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

Laney, Ruth (September 23, 2014). ""The Trouble with Tight Pants"". Country Roads Magazine. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

Boulard, Garry (October 13, 1993). "'JFK' Is More Than a Film In City of Conspiracy Buffs". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

Seal, Mark (December 1991). "Can Hollywood Solve JFK's Murder?". Texas Monthly. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

Reitzes, Dave. "Garrison and JFK Conspiracy Writers". Mcadams.posc.mu.edu. Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

Sylvia Meagher (April 7, 1992). Accessories After the Fact: The Warren Commission, the Authorities, and the Report. Vintage Books. pp. 456–457. ISBN 978-0-679-74315-6.

Gerald Posner, Case Closed, p. 441.

Further reading

Milton E. Brener, The Garrison Case: A Study in the Abuse of Power (Clarkson N. Potter, 1969)

Vincent Bugliosi, Reclaiming History: The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy (W.W. Norton and Company, 2007) – pp. 1347–1436 of the main text and pp. 804–932 of the endnotes are devoted to "Jim Garrison's Prosecution of Clay Shaw and Oliver Stone's Movie JFK"

William Hardy Davis, Aiming for the Jugular in New Orleans (Ashley Books, June 1976)

Sean Egan, Ponies & Rainbows: The Life of James Kirkwood (Bearmanor Media, December 2011)

Paris Flamonde, The Kennedy Conspiracy

Paris Flamonde, The Assassinastion of America (2007)

James Kirkwood, American Grotesque: An Account of the Clay Shaw-Jim Garrison-Kennedy Assassination Trial in New Orleans

Patricia Lambert (September 25, 2000). False Witness: The Real Story of Jim Garrison's Investigation and Oliver Stone's Film JFK. M Evans & Co. ISBN 978-0-87131-920-3.

Mark Lane, Rush to Judgement (Thunder's Mouth Press, 2nd edition, March 1992) ISBN 978-1560250432

Mark Lane, Last Word: My Indictment of the CIA in the Murder of JFK (Skyhorse Publishing, November 2011) ISBN 978-1616084288

Gerald Posner, Case Closed: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Assassination of JFK (New York: Random House Publishers, 1993)

Oliver Stone; Zachary Sklar; Jim Marrs (February 2000). JFK: The Book of the Film. Applause Books. ISBN 978-1-55783-127-9.

James Andrew Savage (June 1, 2010). Jim Garrison's Bourbon Street brawl: the making of a First Amendment milestone. University of Louisiana at Lafayette. ISBN 978-1-887366-95-3.

Harold Weisberg, Oswald in New Orleans: Case for Conspiracy with the C.I.A. (New York: Canyon Books, 1967)

Christine Wiltz, The Last Madam pp. 145–150 ISBN 978-0-571-19954-9

DiEugenio, James (1992). Destiny Betrayed: JFK, Cuba, and the Garrison Case. New York: Sheridan Square Press. ISBN 1-879823-00-4.

Davy, William (1999). Let Justice Be Done: New Light on the Jim Garrison Investigation. Reston, VA: Jordan Pub. ISBN 0-9669716-0-4.

Joan Mellen (2005-10-19). A Farewell to Justice: Jim Garrison, JFK's assassination, and the case that should have changed history. Potomac Books Inc. ISBN 978-1-57488-973-4.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jim_Garrison

On March 1, 1967, New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison arrested and charged New Orleans businessman Clay Shaw with conspiring to assassinate President Kennedy, with the help of Lee Harvey Oswald, David Ferrie, and others. On January 29, 1969, Shaw was brought to trial in Orleans Parish Criminal Court on these charges. On March 1, 1969, a jury took less than an hour to find Shaw not guilty. It remains the only trial to be brought for the assassination of President Kennedy.

Key persons and witnesses

Part of the series on the

Jim Garrison

investigation of the

JFK assassination

People

Jim Garrison

John F. Kennedy

Clay Shaw

David Ferrie

Guy Banister

George de Mohrenschildt

Dean Andrews Jr.

Organizations

Fair Play for Cuba Committee

Friends of Democratic Cuba

Cuban Revolutionary Council

Cuban Democratic

Revolutionary Front

Related articles

Clay Shaw trial

JFK (film)

Single-bullet theory

Clay Bertrand

Assassination conspiracy theories

vte

Jim Garrison, District Attorney of New Orleans, who believed, at various points, that the John F. Kennedy assassination had been the work of Central Intelligence Agency personnel, anti-Castro Cuban exiles,[1][2] "a homosexual thrill killing,"[3][4] and ultra right-wing activists.[5] "My staff and I solved the case weeks ago," Garrison announced in February 1967. "I wouldn't say this if we didn't have evidence beyond a shadow of a doubt."[6][7]

Clay Shaw, a successful businessman, playwright, pioneer of restoration in New Orleans' French Quarter, and director of the International Trade Mart in New Orleans.

David Ferrie, a former Eastern Airlines pilot and associate of Guy Banister. Ferrie drove from New Orleans to Houston on the night of the assassination with two friends, Alvin Beauboeuf and Melvin Coffey.[8] The trip was investigated by the New Orleans Police Department, the Houston Police, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Texas Rangers. These investigative units said that they were unable to develop a case against Ferrie, and Garrison initially accepted their conclusions. Three years later, Garrison became suspicious of the Warren Commission conclusions about the assassination after a chance conversation with Louisiana Senator Russell B. Long.[6] Ferrie died on February 22, 1967, less than a week after news of Garrison's investigation broke in the media. Garrison later called Ferrie "one of history's most important individuals".[9]

Perry Russo, who, after David Ferrie's death, informed Garrison's office that he had known Ferrie in the early 1960s and that Ferrie had spoken about assassinating the President.[10] He became Garrison's main witness when he claimed to have overheard Ferrie plotting the assassination with a white-haired man named Clem Bertrand, whom he later identified in court as Clay Shaw.[11]

Background

The trial was held at the Criminal Courts Building at Tulane & Broad in Mid-City New Orleans

The origins of Garrison's case can be traced to an argument between New Orleans residents Guy Banister and Jack Martin. On November 22, 1963, the day that President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, Banister pistol whipped Martin after a heated exchange. (There are different accounts as to whether the argument was over phone bills or missing files.)[12][13] Over the next few days, Martin told authorities and reporters that Banister had often been in the company of a man named David Ferrie who, Martin said, might have been involved in the assassination of John F. Kennedy.[14] Martin told the New Orleans police that Ferrie knew accused assassin Lee Harvey Oswald going back to when both men had served together in the New Orleans Civil Air Patrol and that Ferrie "was supposed to have been the getaway pilot in the assassination." Martin also said that Ferrie had driven to Dallas the night before the assassination, a trip which Ferrie explained as research for a prospective business venture to determine "the feasibility and possibility of opening an ice skating rink in New Orleans."[15][16]

Some of this information reached New Orleans District Attorney Garrison, who quickly arrested Ferrie and turned him over to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), which interviewed Ferrie and Martin on November 25. Martin told the FBI that Ferrie might have hypnotized Oswald into assassinating Kennedy. The FBI considered Martin unreliable.[17] Nevertheless, the FBI interviewed Ferrie twice about Martin's allegations.[18] The FBI also interviewed about twenty other persons in connection with the allegations, said that it was unable to develop a substantial case against Ferrie, and released him with an apology.[19] (A later investigation, by the United States House Select Committee on Assassinations, concluded that the FBI's "...overall investigation ... at the time of the assassination was not thorough.")[19]

In the autumn of 1966, Garrison began to re-examine the Kennedy assassination. Guy Banister had died of a heart attack in 1964,[20] but Garrison re-interviewed Martin, who told the district attorney that Banister and his associates were involved in stealing weapons and ammunition from armories and in gunrunning. Garrison believed that the men were part of an arms smuggling ring supplying anti-Castro Cubans with weapons."[21]

Journalist James Phelan said Garrison told him that the assassination was a "homosexual thrill killing."[22] As Garrison continued his investigation he became convinced that a group of right-wing activists, which he believed included David Ferrie, Guy Banister, and Clay Shaw (director of the International Trade Mart in New Orleans), were involved in a conspiracy with elements of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to kill President Kennedy. Garrison would later say that the motive for the assassination was anger over Kennedy's foreign policy, especially Kennedy's efforts to find a political, rather than a military, solution in Cuba and Southeast Asia, and his efforts toward a rapprochement with the Soviet Union.[1][2] Garrison also believed that Shaw, Banister, and Ferrie had conspired to set up Oswald as a patsy in the JFK assassination.[23] News of Garrison's investigation was reported in the New Orleans States-Item on February 17, 1967.[6][24]

On February 22, 1967, less than a week after the newspaper broke the story of Garrison's investigation, David Ferrie, then his chief suspect, was found dead in his apartment from a brain aneurysm. Garrison suspected that Ferrie had been murdered despite the coroner's report that his death was due to natural causes.[25] According to Garrison, the day news of the investigation broke, Ferrie had called his aide Lou Ivon and warned that "I'm a dead man".[26]

With Ferrie dead, Garrison began to focus his attention on Clay Shaw, director of the International Trade Mart. Garrison had Shaw arrested on March 1, 1967, charging him with being part of a conspiracy in the John F. Kennedy assassination.

Earlier, Garrison had been searching for a "Clay Bertrand," a man referred to in the Warren Commission report.[27] New Orleans attorney Dean Andrews testified to the Warren Commission that while he was hospitalized for pneumonia, he received a call from "Clay Bertrand" the day after the assassination, asking him to fly to Dallas to represent Oswald.[28][29] According to FBI reports, Andrews told them that this phone call from "Clay Bertrand" was a figment of his imagination.[30] Andrews testified to the Warren Commission that the reason he told the FBI this was because of FBI harassment.[30]

In his book On the Trail of the Assassins, Garrison says that after a long search of the New Orleans French Quarter, his staff was informed by the bartender at the tavern "Cosimo's" that "Clay Bertrand" was the alias that Clay Shaw used. According to Garrison, the bartender felt it was no big secret and "my men began encountering one person after another in the French Quarter who confirmed that it was common knowledge that 'Clay Bertrand' was the name Clay Shaw went by."[31] A February 25, 1967 memo by Garrison investigator Lou Ivon to Garrison states that he could not locate a Clay Bertrand despite numerous inquiries and contacts.[32]

In December 1967, Garrison appeared on a Dallas television program and claimed that a photograph taken in Dealy Plaza immediately after the assassination depicted a federal agent in plain clothes picking up and walking away with a .45 caliber bullet.[33] He said that the bullet was not entered into evidence for the Warren Commission and was proof that another gunman was involved in the assassination.[33] The photograph also showed Dallas Deputy Sheriff Buddy Walthers looking on with a uniformed Dallas policeman. Walthers stated the following week that the photograph was taken approximately 10 minutes after the assassination, and that the finding was "nothing significant". He said that it appeared to be blood on the grass or possibly a piece of skull.[33] Walthers added: "If it had been a bullet, it would have been significant."[33]

When Garrison's evidence was presented to a New Orleans grand jury, Shaw was indicted on a charge that he conspired with Ferrie, Oswald, and others named and charged to murder Kennedy. A three-judge panel upheld the indictment and ordered Shaw to a jury trial.[6]

Trial

On February 6, 1969, Garrison took 42 minutes to read his 15-page opening statement to the jury.[34] Garrison stated that he would prove that Kennedy was shot from multiple locations; that Oswald conspired with Shaw as early as June 1963; that Shaw, Oswald, and Ferrie traveled to Clinton, Louisiana where they were observed by a witness; that Oswald transported the gun identified by the Warren Commission as the assassination rifle to the Texas School Book Depository and that this gun took part in the assassination; that the shot that killed Kennedy came from a different direction; that Oswald escaped from the Texas School Book Depository in a station wagon driven by another man; and that Shaw received mail under the name "Clay Bertrand".[34]

Garrison believed that Clay Shaw was the mysterious "Clay Bertrand" mentioned in the Warren Commission investigation. In the Warren Commission Report, New Orleans attorney Dean Andrews, claimed that he was contacted the day after the assassination by a "Clay Bertrand" who requested that he go to Dallas to represent Oswald.[28][29]

At the trial, the prosecution sought to have entered into evidence a fingerprint card containing Clay Shaw's signature and admission to using the alias "Clay Bertrand." In regard to this, Judge Edward Haggerty, after dismissing the jury, conducted a day-long hearing, in which he ruled the fingerprint card inadmissible. He said that two policemen had violated Shaw's constitutional rights by not permitting the defendant to have his lawyer present during the fingerprinting. Judge Haggerty also announced that Officer Habighorst had violated Miranda v. Arizona and Escobedo v. Illinois by not informing Clay Shaw that he had the right to remain silent. The judge said that Habighorst had violated Shaw's rights by allegedly questioning him about an alias, adding, "Even if he did [ask the question about an alias] it is not admissible." Judge Haggerty exclaimed, "If Officer Habighorst is telling the truth — and I seriously doubt it!" The judge finished with the statement, "I do not believe Officer Habighorst!"[35]

On February 14, Roger Craig, a Dallas deputy sheriff, testified that during the assassination he was standing on the far side of Dealey Plaza across from the Texas School Book Depository. Craig said that immediately afterwards he ran to where the shooting occurred and saw a man that he later identified as Oswald run down the slope away from the building and get into a green station wagon driven by a man with dark complexion. That same day, Carolyn Walther, a Dallas resident, testified that she observed within an open window of the School Book Depository a man in a white shirt holding a gun accompanied by another man wearing a brown suit coat.[36]

Garrison's key witness against Clay Shaw was Perry Russo. Russo testified that he had attended a party at the apartment of anti-Castro activist David Ferrie. At the party, Russo said that Oswald (whom Russo said was introduced to him as "Leon Oswald"), David Ferrie, and "Clem Bertrand" (who Russo identified in the courtroom as Clay Shaw) had discussed killing Kennedy. The conversation included plans for the "triangulation of crossfire" and alibis for the participants.[37] Russo's version of events has been questioned by some historians and researchers, such as Patricia Lambert, once it became known that some of his testimony was induced by hypnotism and by the drug sodium pentothal, sometimes called "truth serum."[38][39]

Moreover, a memo detailing a pre-hypnosis interview with Russo in Baton Rouge, along with two hypnosis session transcripts, had been given to Saturday Evening Post reporter James Phelan by Garrison. There were differences between the two accounts.[40] Both Russo and Assistant D.A. Andrew Sciambra testified under cross examination that more was said at the interview, but omitted from the pre-hypnosis memorandum. James Phelan testified that Russo admitted to him in March 1967 that a February 25 memorandum of the interview, which contained no recollection of an "assassination party," was accurate.[41] In several public interviews, such as one shown in the video The JFK Assassination: The Jim Garrison Tapes, Russo reiterates the same account of an "assassination party" that he gave at the trial.[42][43]

In addition to the issue of Russo's credibility, Garrison's case also included other questionable witnesses, such as Vernon Bundy (a heroin addict), and Charles Spiesel, who testified that he had been repeatedly hypnotized by government agencies.[44] Defenders of Garrison, such as journalist and researcher Jim Marrs, argue that Garrison's case was hampered by missing witnesses that Garrison had sought out. These witnesses included right-wing Cuban exile, Sergio Arcacha Smith, head of the CIA-backed, anti-Castro Cuban Democratic Revolutionary Front in New Orleans, a group that David Ferrie was reputedly "extremely active in",[45] and a group that maintained an office in the same building as Guy Banister.[46] According to Garrison, these witnesses had fled New Orleans to states whose governors refused to honor Garrison's extradition requests.[6][47] Sergio Arcacha Smith had left New Orleans well before Garrison began his investigation[48] and was willing to speak with Garrison's investigators if he was allowed to have legal representation present.[clarification needed][49] Further, witnesses Gordon Novel from Ohio may have been extradited if Garrison pressed the case in Ohio[clarification needed][50] and Sandra Moffett was offered by the defense but opposed by Garrison's prosecution.[clarification needed][51]

The testimony of witnesses who placed Clay Shaw, David Ferrie and Oswald together in Clinton, Louisiana the summer before the assassination has also been deemed not credible by some researchers, including Gerald Posner and Patricia Lambert.[52] When the House Select Committee on Assassinations released its Final Report in 1979, it stated that after interviewing the Clinton witnesses it "found that the Clinton witnesses were credible and significant" and that "it was the judgment of the committee that they were telling the truth as they knew it."[53]

Verdict and juror reaction

At the trial's conclusion — after the prosecution and the defense had presented their cases — the jury took 54 minutes on March 1, 1969, to find Clay Shaw not guilty.

Attorney and author Mark Lane said that he interviewed several jurors after the trial. Although these interviews have never been published, Lane said that some of the jurors believed that Garrison had in fact proven to them that there really was a conspiracy to kill President Kennedy, but that Garrison had not adequately linked the conspiracy to Shaw or provided a motive.[54][55] Author and playwright James Kirkwood, who was a personal friend of Clay Shaw, said that he spoke to several jury members who denied ever speaking to Lane.[56] Kirkwood also cast doubt on Lane's claim that the jury believed there was a conspiracy.[57] In his book American Grotesque, Kirkwood said that jury foreman Sidney Hebert told him: "I didn't think too much of the Warren Report either until the trial. Now I think a lot more of it than I did before."[58]

Later findings, and CIA revelations

On May 8, 1967, the New Orleans States-Item reported that Garrison charged that the CIA and FBI cooperated to conceal the facts of the assassination, and that he planned to seek a Senate inquiry looking into the CIA's role in the Warren Commission's investigation.[59]

Garrison later wrote a book about his investigation of the JFK assassination and the subsequent trial called On the Trail of the Assassins. This book served as one of the main sources for Oliver Stone's movie JFK. In the movie, this trial serves as the back story for Stone's account of the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

Jack Wardlaw, then of the since defunct New Orleans States-Item, an afternoon newspaper, and his fellow journalist Rosemary James, a native of South Carolina, co-authored Plot or Politics, a 1967 book which takes issue with the Garrison investigation as one of political style, rather than substantive evidence. Wardlaw also won an Associated Press award for his story on the death of David Ferrie.[60][61]

In 1979, the House Select Committee on Assassinations stated that available records "lent substantial credence to the possibility that Oswald and David Ferrie had been involved in the same Civil Air Patrol (CAP) unit during the same period of time."[62] Committee investigators found six witnesses who said that Oswald had been present at CAP meetings headed by David Ferrie.[63]

In 1979, the House Select Committee on Assassinations stated in its Final Report that the Committee was "inclined to believe that Oswald was in Clinton, Louisiana in late August, [or] early September 1963, and that he was in the company of David Ferrie, if not Clay Shaw,"[64] and that witnesses in Clinton, Louisiana "established an association of an undetermined nature between Ferrie, Shaw and Oswald less than three months before the assassination".[65]

David Ferrie (second from left) with Lee Harvey Oswald (far right) in the New Orleans Civil Air Patrol in 1955. This photo showing Ferrie and Oswald together only became public after the trial was over.

In 1993, the PBS television program Frontline obtained a group photograph, taken eight years before the assassination, that showed Oswald and Ferrie at a cookout with other Civil Air Patrol cadets. Frontline executive producer Michael Sullivan said, "one should be cautious in ascribing its meaning. The photograph does give much support to the eyewitnesses who say they saw Ferrie and Oswald together in the CAP, and it makes Ferrie's denials that he ever knew Oswald less credible. But it does not prove that the two men were with each other in 1963, nor that they were involved in a conspiracy to kill the president."[66]

In a 1992 interview, Edward Haggerty, who was the judge at the Clay Shaw trial, stated: "I believe he [Shaw] was lying to the jury. Of course, the jury probably believed him. But I think Shaw put a good con job on the jury."[67]

In On the Trail of the Assassins, Garrison states that Shaw had an "extensive international role as an employee of the CIA."[68] In the September 1969 issue of Penthouse, Shaw denied that he had had any connection with the CIA.[69]

During a 1979 libel suit involving the book Coup D'Etat In America, Richard Helms, former director of the CIA, testified under oath that Shaw had been a part-time contact of the Domestic Contact Service of the CIA, where Shaw volunteered information from his travels abroad, mostly to Latin America.[70] Like Shaw, 150,000 Americans (businessmen, and journalists, etc.) had provided such information to the DCS by the mid-1970s.[70] [nb 1] In February 2003, the CIA released documents pertaining to an earlier inquiry from the Assassination Records Review Board about QKENCHANT, a CIA "project used to provide security approvals on non-Agency personnel", that indicated "Clay Shaw received an initial 'five agency' clearance on 23 March 1949", and that "Shaw in all probability was not cleared by the QKENCHANT program."[72]

Reaction

According to The New York Times, the trial of Clay Shaw was "widely described as a circus".[73] Jerry Cohen of the Los Angeles Times said it was "a lengthy comic-opera trial devoid of evidence against the man accused".[74] Burt A. Folkart, also of the Los Angeles Times, called it "a farcical trial."[75] Leading up to the trial, Hugh Aynesworth of Newsweek wrote: "If only no one were living through it—and standing trial for it—the case against Shaw would be a merry kind of parody of conspiracy theories, a can-you-top-this of arbitrarily conjoined improbabilities."[76]

Notes

The United States House Select Committee on Assassinations noted that "25,000 Americans annually provided information to the CIA's Domestic Contacts Division on a nonclandestine basis" and that "such acts of cooperation should not be confused with an actual Agency relationship."[71]

References

Jim Garrison Interview Archived 2019-10-22 at the Wayback Machine, Playboy magazine, Eric Norden, October 1967.

Jim Garrison (November 1988). On the trail of the assassins: my investigation and prosecution of the murder of President Kennedy. Sheridan Square Pubns. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-941781-02-2.

James Phelan, Scandals, Scamps, and Scoundrels, (Random House, 1st Edition 1982) pp. 150-151.

Hugh Aynesworth, "The Garrison Goosechase", Dallas Times Herald, November 21, 1982

"All Those Assassination Suspects". Mcadams.posc.mu.edu. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

Jim Garrison Interview, Playboy magazine, Eric Norden, October 1967.

Milton E. Brener, The Garrison Case (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1969), p. 84.

"David Blackburst Archive: David Ferrie's Houston Trip: JFK assassination investigation: Jim Garrison New Orleans investigation of the John F. Kennedy assassination". Jfk-online.com. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

Eric Norden (October 1967). "Jim Garrison's Playboy interview".

Patricia Lambert, False Witness (New York: M. Evans and Co., 1998), p. 304 fn. 4.

"Perry Russo was Jim Garrison's Conspiracy Witness in the Clay Shaw Trial". Mcadams.posc.mu.edu. 1963-10-07. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

"JFK Record No. 180-10112-10372". Jfk-online.com. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

544 Camp Street and Related Events, House Select Committee on Assassinations - Appendix to Hearings, Volume 10, 13, p. 130.

HSCA Final Assassinations Report, House Select Committee on Assassinations, p. 143.

David Ferrie, House Select Committee on Assassinations - Appendix to Hearings, Volume 10, 12, pp. 112-13.

FBI Interview of David Ferrie, November 25, 1963, Warren Commission Document 75, pp. 288-89.

Gerald L. Posner (1993). Case closed: Lee Harvey Oswald and the assassination of JFK. Random House Inc. p. 428. ISBN 978-0-679-41825-2.

FBI Interview of David Ferrie, 25 November 1963 & 27 November 1963, Warren Commission Document 75, pp. 288-89, 199-200.

544 Camp Street and Related Events, House Select Committee on Assassinations - Appendix to Hearings, Volume 10, 13, p. 126.

Summers, Anthony Not in Your Lifetime, (New York: Marlowe & Company, 1998), p. 226.

Jim Garrison (November 1988). On the trail of the assassins: my investigation and prosecution of the murder of President Kennedy. Sheridan Square Pubns. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-941781-02-2.

"Assassination a Homosexual Thrill Killing". Jfkassassination.net. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

Jim Garrison (November 1988). On the trail of the assassins: my investigation and prosecution of the murder of President Kennedy. Sheridan Square Pubns. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-941781-02-2.

New Orleans States-Item, February 17, 1967

Jim Garrison (November 1988). On the trail of the assassins: my investigation and prosecution of the murder of President Kennedy. Sheridan Square Pubns. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-941781-02-2.

Jim Garrison (November 1988). On the trail of the assassins: my investigation and prosecution of the murder of President Kennedy. Sheridan Square Pubns. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-941781-02-2.

Commission Exhibit No. 1931, Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 23, p. 726.

Testimony of Dean Adams Andrews, Jr., Warren Commission Hearings, Volume 11, p. 331.

Anthony Summers (September 1998). Not in your lifetime. Marlowe & Co. p. 241. ISBN 978-1-56924-739-6.

Testimony of Dean Adams Andrews, Jr., Warren Commission Hearings, Volume 11, p. 334.

Jim Garrison (November 1988). On the trail of the assassins: my investigation and prosecution of the murder of President Kennedy. Sheridan Square Pubns. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-0-941781-02-2.

"Lou Ivon: No "Clay Bertrand"". Mcadams.posc.mu.edu. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

McGraw, Preston (December 14, 1967). "Deputy Sheriff Doubts Garrison Bullet Claim". Madera Daily Tribune. Vol. 76, no. 151. Madera, California: Dean S. Lesher. UPI. p. 3. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

"Garrison: Not Oswald". St. Petersburg Times. St. Petersburg, Florida. UPI. February 7, 1969. p. 1. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

James Kirkwood, American Grotesque (New York: Harper, 1992), pp. 353-59

"Dallas Deputy Links 'Latin" With Oswald At Shaw Trial; Witness Testifies Station Wagon Drove Accused Assassin From Scene". The Blade. Toledo, Ohio. Reuters. February 15, 1969. p. 2. Retrieved April 19, 2017.

Testimony of Perry Raymond Russo, State of Louisiana vs. Clay L. Shaw, February 10, 1969.

"Memorandum, February 28, 1967, Interview with Perry Russo at Mercy Hospital on February 27, 1967". Retrieved 2010-09-17.

Lambert, False Witness, pp.72-73.

Reitzes, Dave. "Way Too Willing Witness". Marquette University. Retrieved 2013-11-23.

James Phelan, "Rush to Judgment in New Orleans", Saturday Evening Post, May 6, 1967.

The Lighthouse Report, "The Last Testament of Perry Raymond Russo" Archived 2008-02-05 at the Wayback Machine, Will Robinson, 10 October 1992.

The JFK Assassination: The Jim Garrison Tapes, John Barbour, 1992.

"Attempt to Use Insane Witness Blows Up In Garrison's Face". Mcadams.posc.mu.edu. 1969-02-08. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

544 Camp Street and Related Events, House Select Committee on Assassinations - Appendix to Hearings, Volume 10, 13, p. 127.

David Ferrie, House Select Committee on Assassinations - Appendix to Hearings, Volume 10, 12, p. 110.

Jim Garrison (November 1988). On the trail of the assassins: my investigation and prosecution of the murder of President Kennedy. Sheridan Square Pubns. pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-0-941781-02-2.

Warren Commission Exhibit No. 1414 (Warren Commission Hearings Vol. XXII, 828-30). "Arcacha moved from New Orleans to Miami in October 1962, and from Miami to Houston in January 1963, and took a job as an air conditioning salesman in March 1963" (House Select Committee Statement of Mrs. Sergio Arcacha Smith, undated; David Blackburst, Newsgroup post of November 29, 1997).

"citing to New Orleans States-Item, May 23, 1967". Mcadams.posc.mu.edu. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

Edward J. Epstein, The Assassination Chronicles, New York, 1992, p. 248

Shaw trial transcript, Feb. 6, 1969, pp. 5-13

"Impeaching Clinton by Dave Reitzes". Mcadams.posc.mu.edu. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

"I.C.". Report of the Select Committee on Assassinations of the U.S. House of Representatives. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. 1979. p. 142.

Mark Lane. Plausible Denial: Was the CIA Involved in the Assassination of JFK?, (New York: Thunder's Mouth Press, 1991), p. 221.

Jordan Publishing; William Davy (May 1999). Let Justice Be Done: New Light on the Jim Garrison Investigation. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-9669716-0-6.

James Kirkwood. American Grotesque (New York: Harper, 1992), p. 510

summary of Kirkwood's research and juror responses, James Kirkwood. American Grotesque (New York: Harper, 1992), p. 557.

James Kirkwood. American Grotesque (New York: Harper, 1992), p. 511.

"To Request Senate Probe In Kennedy Assassination". The Southeast Missourian. Cape Girardeau, Missouri. AP. May 9, 1967. p. 10. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

Jack Wardlaw and Rosemary James, Plot or Politics: The Garrison Case & Its Cast, p. 84. Pelican Publishing Company, 1967. 1967. ISBN 9781589809185. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

"Ed Anderson, "Former Times-Picayune political reporter, capital bureau chief Jack Wardlaw dies," January 6, 2012". New Orleans Times-Picayune. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

Oswald, David Ferrie and the Civil Air Patrol, House Select Committee on Assassinations, Volume 9, 4, p. 110.

Oswald, David Ferrie and the Civil Air Patrol, House Select Committee on Assassinations, Volume 9, 4, pp. 110-115.

HSCA Final Assassinations Report, House Select Committee on Assassinations, p. 145

HSCA Final Assassinations Report, House Select Committee on Assassinations, p. 143

PBS Frontline "Who Was Lee Harvey Oswald", broadcast on PBS stations, November 1993 (various dates). Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

Edward Haggerty interviewed in the documentary Beyond "JFK": The Question of Conspiracy

Jim Garrison (November 1988). On the trail of the assassins: my investigation and prosecution of the murder of President Kennedy. Sheridan Square Pubns. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-941781-02-2.

Phelan, James (September 1969). "Clay Shaw; Exclusive Penthouse Interview" (PDF). Penthouse. p. 36. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

Holland, Max (2001). "The Lie That Linked CIA to the Kennedy Assassination". Studies in Intelligence. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency: Center for the Study of Intelligence (Fall-Winter 2001, 11). Archived from the original on June 13, 2007. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

"I.C.". Report of the Select Committee on Assassinations of the U.S. House of Representatives. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. 1979. p. X.

"ARRB REQUEST: CIA-IR-06, QKENCHANT" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. 1996-05-14. p. 5. Retrieved 2013-11-25.

Lambert, Bruce (October 22, 1992). "Jim Garrison, 70, Theorist on Kennedy Death, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

Cohen, Jerry (January 3, 1971). "Kirkwood's Clay Shaw Book Will Be The Definitive Work". The Tuscaloosa News. Vol. 153, no. 3. Tuscaloosa-Northport, Alabama. p. 4, Section D. Retrieved October 23, 2015 – via the Los Angeles Times.

Folkart, Burt A. (October 22, 1992). "Jim Garrison; D.A. Challenged JFK Assassination Report". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

Aynesworth, Hugh (February 3, 1969). "Odds Favor Conviction Of Jim Garrison's 'Patsy'". The Pittsburgh Press. Vol. 85, no. 220. p. 17. Retrieved October 23, 2015 – via Newsweek Feature Service.

Further reading

Milton Brener, The Garrison Case: A Study in the Abuse of Power.

Jordan Publishing; William Davy (May 1999). Let Justice Be Done: New Light on the Jim Garrison Investigation. ISBN 978-0-9669716-0-6.

Jim Garrison, A Heritage of Stone (Putnam Publishing Group, 1970) ISBN 978-0-399-10398-8

Jim Garrison (1991-12-01). On the Trail of the Assassins. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-0-446-36277-1.

James Kirkwood (1992-11-05). American grotesque: an account of the Clay Shaw-Jim Garrison Kennedy assassination trial in the city of New Orleans. Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-097523-4.

Patricia Lambert (2000-09-25). False Witness: The Real Story of Jim Garrison's Investigation and Oliver Stone's Film JFK. M Evans & Co. ISBN 978-0-87131-920-3.

Joan Mellen (2005-10-19). A farewell to justice: Jim Garrison, JFK's assassination, and the case that should have changed history. Potomac Books Inc. ISBN 978-1-57488-973-4.

Anthony Summers (September 1998). Not in your lifetime. Marlowe & Co. ISBN 978-1-56924-739-6.

Harold Weisberg, Oswald in New Orleans: Case for Conspiracy with the C.I.A. (New York: Canyon Books, 1967) ISBN B-000-6BTIS-S

External links

Louisiana v. Clay Shaw (1969) trial transcript

Orleans Parish Grand Jury transcripts

Esquire December 1968 interview with Clay Shaw, James Kirkwood

Jim Garrison and New Orleans

Penthouse interview with Clay Shaw

Small Lies, Big Lies, and Outright Whoppers

Transcript of Perry Russo's Hypnotic Interrogation of March 1, 1969.

Transcript of Perry Russo's Hypnotic Interrogation of March 12, 1969.

JFK Online: Jim Garrison audio resources - mp3s of Garrison speaking

CIA Counterintelligence Director James Angleton Spying on a Garrison Witness, Real History Archives

Garrison's Case for Conspiracy, Real History Archives

Garrison Guilty: Another Case Closed, The New York Times Magazine, August 6, 1995

Garrison's Case Finally Coming Together by Martin Shackelford

vte

Assassination of John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy Lee Harvey Oswald

Assassination

Assassination rifle Timeline J. D. Tippit John Connally Nellie Connally Jacqueline Kennedy

Pink Chanel suit James Tague William Greer Roy Kellerman Clint Hill Zapruder film

Abraham Zapruder Dealey Plaza Texas School Book Depository

Sixth Floor Museum Presidential limousine Parkland Hospital Witnesses Marie Muchmore Orville Nix Three tramps Babushka Lady Badge Man Umbrella man

Aftermath

Autopsy Reactions Johnson inauguration Jack Ruby Ruby v. Texas Dictabelt recording Conspiracy theories

CIA Single-bullet theory 1992 Assassination Records Act In popular culture Robert N. McClelland (surgeon) Charles Baxter (physician) Malcolm Perry (physician) Earl Rose (coroner) Dallas memorial

State funeral

Foreign dignitaries Burial site and Eternal Flame Black Jack (horse)

Investigations

Warren Commission Jim Garrison investigation House Select Committee on Assassinations Researchers

Category

Categories:

1969 in American law1969 in Louisiana1960s trialsAssassination of John F. KennedyCriminal trials that ended in acquittalConspiracy theories in the United States20th-century American trials

-

1:04:49

1:04:49

THE RICH VERNADEAU SHOW

1 year agoJFK ASSASSINATION: Jake Carter and Gayle Nix Jackson DAILY TALK SHOW

39 -

1:58:46

1:58:46

RabbitHoleRadio

1 year agoCol. L Fletcher Prouty & Jim Garrison on The JFK Assassination and The Evidence of A Conspiracy

3482 -

0:58

0:58

GET2IT!

1 year agoJFK ASSASSINATION: Lee Harvey Oswald & RUBY'S CONFESSION

16 -

45:21

45:21

TheOmniCoalition

1 year agoJoan of Arc's Trial, Malcolm X Assassinated, Alan Rickman and More! - TDH 2/21/23

71 -

1:59:10

1:59:10

RabbitHoleRadio

1 year agoThe JFK Assassination: A Case For Conspiracy

4353 -

7:16

7:16

TomOYoungjohn

1 year agoJAG Sentences Jerome Adams to Death - Michael Baxter RealRawNews 2-12-23

1.48K7 -

25:25

25:25

Kennedy Americans podcast

6 months agoJFK Assassination: Case NOT Closed!

1691 -

25:24

25:24

RFK Jr. News Channel

6 months agoJFK Assassination: Case NOT Closed!

4785 -

1:51

1:51

vinnyhearns

11 months agoJean Hill JFK Assassination Eyewitness Testimony

16 -

15:09

15:09

InfoWars Films +

11 months agoE. Howard Hunt JFK Assassination Confession

2.39K1